In this article I introduce the nascent field of Text-Oriented Programming (TOP), commonly used when building applications that use Large Language Models (LLMs). TOP poses new challenges for application design, DevOps, robustness and security.

This article is informed by my hands-on experience building Finchbot, an application that converts natural language text to a symbolic domain model.

Definition

Text-Oriented Programming (TOP) is required when the primary interface to an application is natural language, and the application is using non-deterministic machine learning models to process the natural language input, or using generative AI to produce natural language output.

Traditional Approach

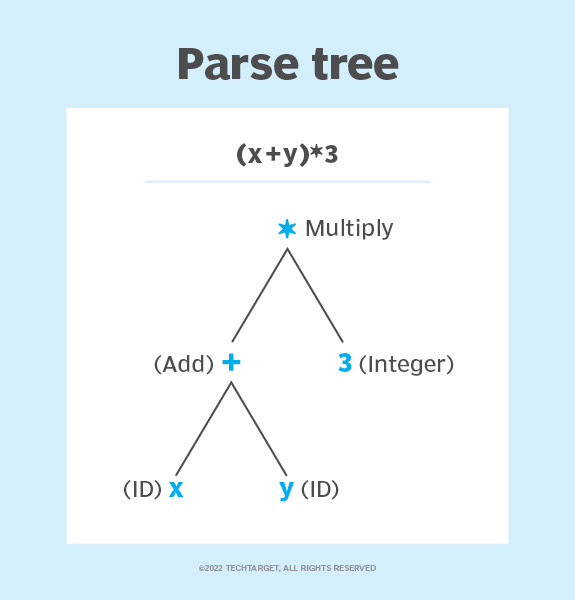

In a traditional symbolic computer program that is processing textual input the programmer defines a grammar that produces an abstract (or concrete) syntax tree from the textual input. The conversion from text input to a symbolic syntax tree is deterministic. It is often challenging to fully test the grammar (typically requiring hundreds of sample inputs, and asserting that the produced syntax tree is correct), but the problem is well-understood and tractable.

Quick-and-dirty application of regular expressions to text input fall into the same category. In both cases, the programmer defines the expected patterns of input and the symbolic syntax tree that should be created from the input. The mapping from input to output is deterministic and (relatively) easy for a developer experienced in grammar design to reason about.

Inputs that fall outside of the input patterns defined by the grammar will fail to parse and will be rejected, often with a helpful error message.

There’s a long history of adversarial attacks against parsers, from URL encoding attacks to hiding executable scripts inside HTML, or other formats that might be supplied by end users.

Textual output is created from a symbolic syntax tree by visiting the tree and converting it to natural language, or back into a valid input.

TOP Approach

When using TOP the programmer cedes control over the parsing of textual input, and generation of textual output, to a non-deterministic, black-box, machine learning model (often an LLM). The LLM encodes the expected mapping from inputs to excepted outputs in billions of artificial neutrons. The programmer is choosing to sacrifice determinism, performance/cost for the ability to deal with a much wider variety of natural language inputs. LLMs encode general domain knowledge (and knowledge of dozens of natural languages) that they can outperform hand-created grammar patterns for some use cases.

- Text –> LLM –> Symbols (AST)

- Symbols (AST) –> LLM –> Text

TOP Challenges

Adopting TOP creates some new programming challenges:

Non-Determinism

A given input text may produce several symbolic representations. The programmer typically choses the most likely of these (using the temperature and top-p parameters of the LLM) but the alternative representations are there, and text input X on Monday may produce symbolic representation A, and on Tuesday may produce alternative representation A’. This can be disconcerting for users used to dealing with deterministic parsing.

Model Drift

Another source of non-determinism (at least from the programmer’s perspective) is that they often don’t control the deployment lifecycle of the LLM. New versions of the LLM will be deployed, sometimes at short notice, and they could radically improve, or degrade, the quality of symbolic output. In some cases the programmer can “pin” their application to a specific version of the LLM as a short-term fix.

Parsing Model Output

The LLM converts the input text to an output symbolic representation, however that output representation is also represented as text, often in a structured format such as JSON, markdown, CSV or YAML. These structured formats are often interspersed with natural language explanations of the output, with the LLM expanding on what it has generated for a human consumer. When the consumer is a program the output must be parsed and validated.

Small changes to the output from the LLM may break the parsing of its response. Of course, you could create a parser grammar for this, or recursively apply an LLM!

Experience shows that when a new version of the LLM model is deployed (e.g. changes to ChatGPT) the format of the output text often changes in subtle, but important ways. Programs must be robust to changes in LLM output, or failure to generate output.

Latency

LLM latency is orders of magnitude higher than using a traditional parser. User Experience design of the application must take this into account, to ensure that the application remains responsive. Cloud hosted LLMs may produce output in a second, ten seconds or simply time-out.

Prompt Engineering

To make calls to the LLM a prompt must be constructed, which typically embeds input from the end user. Constructing prompts is more art than science and the new discipline of prompt engineering is the process of building a set of application specific prompts that are robust and work with a wide variety of user inputs. Frameworks such as LangChain can be used by developers to manage and test their prompts.

Again, prompts are very sensitive to LLM version deployments: a set of prompts that work well with one version of an LLM may need to be updated for a new version of the same model.

Prompt Injection Attacks

As prompts include content from the end user (which should not be trusted!) it is trivial for the end user to inject adversarial content (prompt injection) to get the LLM to produce undesirable content. Unlike with SQL injection attacks however there is no easy way to “escape” the end user’s content to ensure that it cannot harm the system. The openness and generality of the natural language interface makes this essentially impossible.

It is therefore vital to check the symbolic output from the LLM before flowing it to downstream API calls, or systems with side-effects in the real-world. If the input to the LLM is untrusted (which in the vast majority of cases it is) then the symbolic output from the LLM must also be considered to be similarly untrusted. If the output is even displayed, then there is reputational risk, and disclaimers may be required.

Cost

Using an LLM to convert natural language to symbols is not free, in environmental terms (CPU cycles, cooling, water usage) as well as in dollars. You should review your capacity planning and cost estimation to ensure that using an LLM makes sense from a cost perspective.

Trust and Privacy

LLMs are often cloud hosted services (OpenAI, Anthropic, Bard…) meaning that sensitive end user data will be flowing outside of your application’s control, potentially across geographical borders. You must be transparent with your end users about who you are sharing their data with, and how it will be used by your application as well as those 3rd-parties.

Summary

Moving from a parser implemented in a strongly-typed programming language (with static type checking) to TOP, where untyped natural language is flowing around the system, and conversion from text to symbols is non-deterministic, is a jarring experience for most developers. It requires a cultural and philosophical reset on how to think about inputs, outputs and computation.

The challenges are real but the rewards can be substantial for developers that embrace this major breakthrough in Human Computer Interaction.

Leave a comment